|

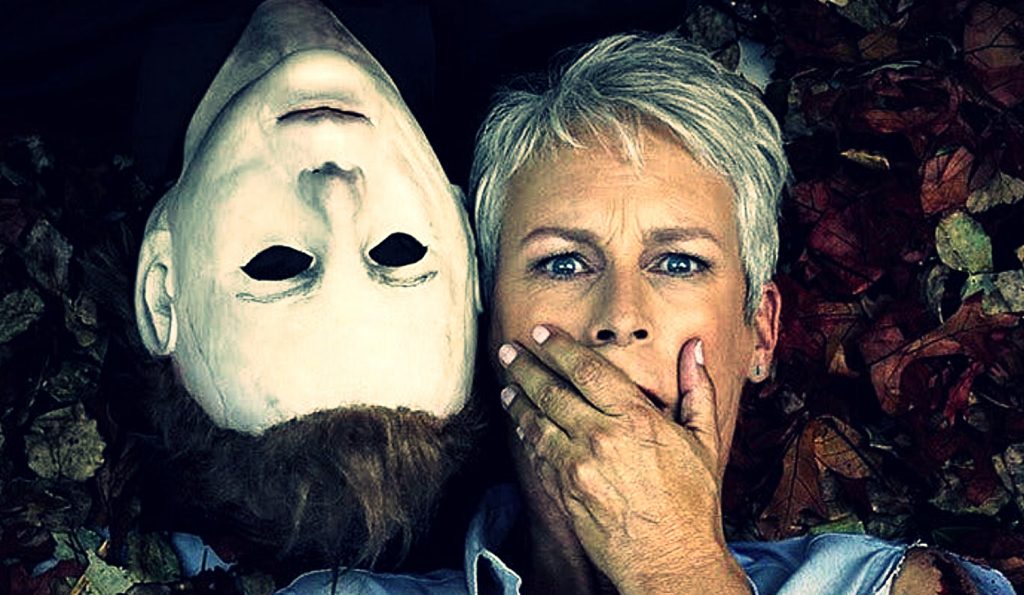

Today we have a guest post from friend of the blog Samuel Maleski, you can read more of his work at downtime2017.wordpress.com and find him on twitter at @LookingForTelos . It's a really interesting look at the Halloween movies, and I'm lucky I get to share it here. Enjoy! Halloween, Triumphant: |

James Wylder

Poet, Playwright, Game Designer, Writer, Freelancer for hire. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed